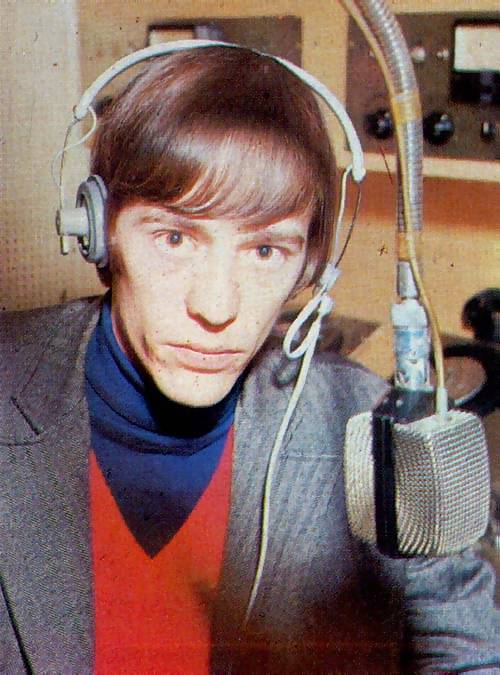

Questa è l’intervista integrale (che mi impegno a tradurre prossimamente) di Tommy Vance a Roger Waters per il programma Friday Rock Show (BBC RADIO ONE) andato in onda il 30 Novembre 1979.

[Nota: i titoli tra le parentesi quadre sono i brani trasmessi in radio tra una serie di domande e l’altra.](TV=Tommy Vance / RW=Roger Waters)

TV: Where did the idea come from?

RW: Well, the idea for ‘The Wall’ came from ten years of touring, rock shows, I think, particularly the last few years in ’75 and in ’77 we were playing to very large audiences, some of whom were our old audience who’d come to see us play, but most of whom were only there for the beer, in big stadiums, and, er, consequently it became rather an alienating experience doing the shows. I became very conscious of a wall between us and our audience and so this record started out as being an expression of those feelings.

TV: But it goes I think a little deeper than that, because the record actually seems to start at the beginning of the character’s life.

RW: The story has been developed considerably since then, this was two years ago [1977], I started to write it, and now it’s partly about a live show situation–in fact the album starts off in a live show, and then it flashes back and traces a story of a character, if you like, of Pink himself, whoever he may be. But initially it just stemmed from shows being horrible.

TV: When you say “horrible” do you mean that really you didn’t want to be there?

RW: Yeah, it’s all, er, particularly because the people who you’re most aware of at a rock show on stage are the front 20 or 30 rows of bodies. And in large situations where you’re using what’s euphemistically called “festival seating” they tend to be packed together, swaying madly, and it’s very difficult to perform under those situations with screaming and shouting and throwing things and hitting each other and crashing about and letting off fireworks and you know?

TV: Uh-huh.

RW: I mean having a wonderful time but, it’s a drag to try and play when all that’s going on. But, er, I felt at the saem time that it was a situation we’d created ourselves through our own greed, you know, if you play very large venues…the only real reason for playing large venues is to make money.

TV: But surely in your case it wouldn’t be economic, or feasible, to play a small venue.

RW: Well, it’s not going to be on when we do this show, because this show is going to lose money, but on those tours that I’m talking about; the ’75 tour of Europe and England and the ’77 tour of England and Europe and America as well, we were making money, we made a lot of money on those tours, because we were playing big venues.

TV: What would you like the audience to do–how would you like the audience to react to your music?

RW: I’m actually happy that they do whatever they feel is necessary because they’re only expressing their response to what it’s like, in a way I’m saying they’re right, you know, that those shows are bad news.

TV: Um.

RW: There is an idea, or there has been an idea for many years abroad that it’s a very uplifting and wonderful experience and that there’s a great contact between the audience and the perfomrers on the stage and I think that that is not true, I think there’ve been very many cases, er, it’s actually a rather alienating experience.

TV: For the audience?

RW: For everybody.

TV: It’s two and a half years since you had an album out and I think people will be interested in knowing how long it’s taken you to develop this album.

RW: Right, well we toured, we did a tour which ended I think in July or August ’77 and when we finished that tour in the Autumn of that year, that’s when I started writing it. It took me a year, no, until the next July, working on my own, then I had a demo, sort of 90 minutes of stuff, which I played to the rest of the guys and then we all started working on it together, in the October or November of that…October ’78, we started working on it.

TV: And you actually ceased recording, I think, in November of this year? [1979]

RW: Yeah. We didn’t start recording until the new year, well, till April this year, but we were rehearsing and fiddling about obviously re-writing a lot. So it’s been a long time but we always tend to work very slowly anyway, because, it’s difficult.

TV: The first track is “In the Flesh”?

RW: Yeah.

TV: This actually sets up what the character has become.

RW: Yes.

TV: At the end.

RW: Couldn’t have put it better myself! It’s a reference back to our ’77 tour which was called “Pink Floyd in the Flesh.”

TV: And then you have a track called “The Thin Ice.”

RW: Yeah.

TV: Now, this is I think, at the very very *beginning* of the character; call the character “Pink”…

RW: Right.

TV: …the very beginning of Pink’s [simultaneously] life?

RW: Yeah, absolutely, yeah. In fact at the end of “In the Flesh” er, you hear somebody shouting “roll the sound effects” da-da-da, and er, you hear the sound of bombers, so it gives you some indication of what’s happening. In the show it’ll be much more obvious what’s going on. So it’s a flashback, we start telling the story. In terms of this it’s about my generation.

TV: The war?

RW: Yeah. War-babies. But it could be about anybody who gets left by anybody, if you like.

TV: Did that happen to you?

RW: Yeah, my father was killed in the war.

[IN THE FLESH] [THE THIN ICE]

TV: And then comes “Another Brick in the Wall, Part I”…which is actually about the father who’s gone?

RW: Yeah.

TV: Though the father in the album “has flown across the ocean…”

RW: Yeah.

TV: …now the assumption from listening to that would be that he’s gone away to somewhere else.

RW: Yeah, well, it could be, you see it works on various levels–it doesn’t have to be about the war–I mean it *should* work for any generation really. The father is also…I’m the father as well. You know, people who leave their families to go and work, not that I would leave my family to go and work, but lots of people do and have done, so it’s not meant to be a simple story about, you know, somebody’s getting killed in the war or growing up and going to school, etc., etc., etc. but about being left, more generally.

TV: “The Happiest Days of our Lives” is, er, a complete condemnation, as I see it, as I’ve heard it in the album, of somebody’s scholastic career.

RW: Um. My school life was very like that. Oh, it was awful, it was really terrible. When I hear people whining on now about bringing back Grammar schools it really makes me quite ill to listen to it. Because I went to a boys Grammar school and although… want to make it plain that some of the men who taught (it was a boys school) some of the men who taught there were very nice guys, you know I’m not…it’s not meant to be a blanket condemnation of teachers everywhere, but the bad ones can really do people in–and there were some at my school who were just incredibly bad and treated the children so badly, just putting them down, putting them down, you know, all the time. Never encouraging them to do things, not really trying to interest them in anything, just trying to keep them quiet and still, and crush them into the right shape, so that they would go to university and “do well.”

[ANOTHER BRICK: ONE]

[THE HAPPIEST DAYS OF OUR LIVES]

[ANOTHER BRICK: TWO]

TV: What about the track “Mother”? What sort of a mother is this mother?

RW: Over-protective; which most mothers are. If you can level one accusation at mothers it is that they tend to protect their children too much. Too much and for too long. That’s all. This isn’t a portrait of my mother, although some of the, you know, one or two of the things in there apply to her as well as to I’m sure lots of other people’s mothers. Funnily enough, lots of people recognize that and in fact, a woman that I know the other day who’d heard the album, called me up and said she’d liked it. And she said that listening to that track made her feel very guilty and she’s got herself three kids, and I wouldn’t have said she was particularly over-protectice towards her children. I was interested, you know, she’s a woman, of well, my age, and I was interested that it had got through to her. I was *glad* it had, you know, if you can…if it means…

[MOTHER]

TV: And then comes the track “Goodbye blue sky.” What is actually happening at this stage in Pink’s life?

RW: Since we compiled the album I haven’t really clearly tried to think my way through it, but I know that this area is very confusing. I think the best way to describe it is as a recap if you like of side one. (This is the start of side two.) And you could look upon “Goodbye blue sky” as a recap of side one. So, yes, it’s remembering one’s childhood and then getting ready to set off into the rest of one’s life.

[GOODBYE BLUE SKY]

TV: And then comes the track “What shall we do now.” The assumption this would be when the emergent adult…

RW: That’s right. Now that’s the track that’s not on the album. It was quite nice! In fact I think we’ll do it in the show. But it’s quite long, and this side was too long, and there was too much of it, it’s basically the same as “Empty spaces” and we’ve put “Empty spaces” where “What shall we do now” is.

TV: Because without those words listening to the album….

RW: Yeah it makes less sense.

TV: Well it’s not so much that it makes less sense it just means that there’s a period in Pink’s life that isn’t indicated. I mean he jumps from the recap of side one immediately into “Young lust.”

RW: Right. No, he doesn’t, he goes into “Empty spaces” and the lyrics there are very similar to the first four lines of “What shall we do now?” But what’s different really is this list–“shall we buy a new guitar, drive a more powerful car, work right through the night,” you know, and all that stuff.

TV: “Give up meat, rarely sleep, keep people as pets.”

RW: Right. It’s just about the ways that one protects oneself from one’s isolation by becoming obsessed with other people’s ideas. Whether the idea is that it’s good to drive…have a powerful car, you know, or whether you’re obsessed with the idea of being a vegetarian…adopting somebody else’s criteria for yourself. Without considering them from a position of really being yourself; on this level the story is extremely simplistic, I hope that on other levels there are less tangible, more effective things that come through. I think it’s ok in a show, where you only hear the words, you probably won’t hear the words at all the way rock and roll shows get produced.

TV: But they’re there obviously if you need them?

RW: Yeah. That’s why we didn’t go into a great panic about trying to change all the inner bags and things, I think it’s important that they’re there so that people can read them. Equally I think it’s important that people know why they’re there, otherwise I agree it’s terribly confusing.

TV: And then you come to this track which is called “Young lust.” As far as Pink the rock and roll star, and Roger Waters the writer, was there ever a young lust section of your life?

RW: Well, yes, I suppose, actually, yes it did happen to me, that was like me. But I would never have said it, you see, I’d never have come out with anything like that, I was much too frightened. When I wrote this song “Young lust” the words were all quite different, it was about leaving school and wandering around town and hanging around outside porno movies and dirty bookshops and being very interested in sex, but never actually being able to get involved because of being too frightened actually. Now it’s completely different, that was a function of us all working together on the record, particularly with Dave Gilmour and Bob Ezrin who, we co-produced the album together, the three of us co-produced it. “Young Lust” is a pastiche number. It reminds me very much of a song we recorded years and years ago called “The Nile Song,” it’s very similar, Dave sings it in a very similar way. I think he sings “Young Lust” terrific, I love the vocals. But it’s meant to be a pastiche of any young rock and roll band out on the road.

[EMPTY SPACES]

[YOUNG LUST]

RW: I think it’s great; I love that operator on it, I think she’s wonderful. She didn’t know what was happening at all, the way she picks up on..I mean it’s been edited a bit, but the way she picks up, all that stuff about “is there supposed to be someone else there beside your wife” you know I think is amazing, she really clicked into it straight away. She’s terrific!

TV: And then comes “One of My Turns.”

RW: Yes, so then the idea is that we’ve leapt somehow a lot of years, from “Goodbye Blue Sky” through “What Shall we do Now” which doesn’t exist on the record anymore, and “Empty Spaces” into “Young Lust” that’s like a show; we’ve leapt into a rock and roll show, somewhere on into our hero’s career. And “One of My Turns” is supposed to be his response to a lot of aggro [aggression] in his life and not having ever got anything together, although he’s married, well, no he has got things together, but he’s been married, and he’s just had a…he’s just splitting up with his wife, and in response he takes another girl up to his hotel room.

TV: And he really is, “he’s got everything but nothing.”

RW: He’s had it now, he’s definitely a bit “yippee” now, and “One of My Turns” is just, you know, him coming in and he can’t relate to this girl either, that’s why he just turns on the TV, they come into the room and she starts going on about all the things he’s got and all that he does is just turn on the TV and sit there, and he won’t talk to her.

[ONE OF MY TURNS]

TV: Then comes a period in “Don’t Leave Me Now” when he realizes the state that he’s in, he still feels, if you like, aggressive, completely depressed, thoroughly paranoid, and very lonely, and but very lonely, to the point of suicide.

RW: Yeah, well, not quite…but yes it is a very depressing song. I love it! I really like it!

TV: There’s this line in the song “to beat you to a pulp on a Saturday night.”

RW: Yeah.

TV: Now that’s just, I don’t know how to phrase that, but it really is the depths, if you like, of deprived depravity.

RW: Well a lot of men and women do get involved with each other for lots of wrong reasons, and they do get very aggressive towards each other, and do each other a lot of damage. I, of course, have never struck a woman, as far as I can recall, Tommy, and I hope I never do, but a lot of people have, and a lot of women have struck men as well, there is a lot of violence in relationships often that aren’t working. I mean this is obviously an extremely cynical song, I don’t feel like that about marriage now.

TV: But you did?

RW: Er, this is one of those difficult things where a small percentage of this is autobiographical, and all of it is rooted in my own experience, but it isn’t my autobiography, although it’s rooted within my own experience, like any writing, some of it’s me and an awful lot of it is what I’ve observed.

TV: But there’s also a lot of fundamental truth in it.

RW: Well I hope so, if you look and see things and if they ring true, then those are the kind of things, if you’re interested in writing songs of books or poems or writing anything then those are the things that you try and write down, because those are the things that are interesting, and those are the things that will touch other people, which is what writing is all about, you know. Some people have a need to write down their own feelings in the hope that other people will recognize them, and derive some worth from them, whether it’s a feeling of kinship or whether it makes them happy, or whatever, they will derive something from it.

[DON’T LEAVE ME NOW]

[ANOTHER BRICK: 3]

TV: “Another Brick 3” “I don’t need no arms around around me,” he seems to be in a position whereby he’s no longer confused, in other words he’s more confident. Then comes the track “Goodbye Cruel World.” What is happening here?

RW: Well, what’s happening is; from the beginning of “One of My Turns” where the door opens, there, through to the end of side three, the scenario is an American hotel room, the groupie leaves at the end of “One of My Turns” and then “Don’t Leave Me Now” he sings which is to anybody, it’s not to her and it’s not really to his wife, it’s kind of to anybody; if you like it’s kind of men to women in a way, from that kind of feeling, it’s a kind of very guilty song as well. Anyway at the end of that, there he is in his room with his TV and there’s that symbolic TV smashing, and then he resurges a bit, out of that kind of violence, and then he sings this loud saying “all you are just bricks in the wall,” I don’t need anybody, so he’s convincing himself really that his isolation is a desirable thing, that’s all.

TV: But how is he in that moment of time, when he says “goodbye cruel world”?

RW: That’s him going catatonic if you like, that final and he’s going back and he’s just curling up and he’s not going to move. That’s it, he’s had enough, that’s the end.

[GOODBYE CRUEL WORLD]

RW: In the show, we’ve worked out a very clever mechanical system so that we can complete the middle section of the wall, building downwards, so that we get left with a sort of triangular shaped hole that we can fill in bit by bit. Rather than filling it in at the top, there’ll be this enormous wall across the auditorium, we’ll be filling in this little hole at the bottom. The last brick goes in then, as sings goodbye at the end of the song. That is the completion of the wall. It’s been being built in my case since the end of the Second World War, or in anybody else’s case, whenever they care to think about it, if they feel isolated or alienated from other people at all, you know, it’s from whenever you want.

TV: So it would be accurate to say that at that moment in time he’s discovered exactly where he’s at, and the wall is complete, in other words, his character, via all the experiences he’s had, has finally, in his eyes anyway, been completed.

RW: He’s nowhere.

TV: And then comes the beginning of side three, which actually starts with a different song than on the sleeve.

RW: Yeah. Bob Ezrin called me up and he said I’ve just listened to side three and it doesn’t work. In fact I think I’d been feeling uncomfortable about it anyway. I thought about it and in a couple of minutes I realized that “Hey You” could conceptually go anywhere, and it would make a much better side if we put it at the front of the side, and sandwiched the middle theatrical scene, with the guy in the hotel room, between an attempt to re-establish contact with the outside world, which is what “Hey You” is; at the end of the side which is, well, what we’ll come to. So that’s why those lyrics are printed in the wrong place, is because that decision was made very late; I should explain at this point, the reason that all these decisions were made so late was because we’d promised lots of people a long time ago that we would finish this record by the beginning of November, and we wanted to keep that promise.

TV: Well the guy is now behind the wall…

RW: Yeah, he’s behind the wall a) symbolically and b) he’s locked in a hotel room, with a broken window that looks onto the freeway, motorway.

TV: And now what’s he going to do with his life?

RW: Well, within his mind, because “Hey You” is a cry to the rest of the world, you know saying hey, this isn’t right, but it’s also, it takes a narrative look at it, when it goes…Dave sings the first two verses of it and then there’s an instrumental passage and then there’s a bit that goes “but it was only fantasy” which I sing, which is a narration of the thing; “the wall was too high as you can see, no matter how he tried he could not break free, and the worms ate into his brain.” The worms. That’s the first reference to worms…the worms have a lot less to do with the peice than they did a year ago; a year ago they were *very* much a part of it, if you like they were my symbolic representation of decay. Because the basic idea the whole thing really is that if you isolate yourself you decay.

[HEY YOU]

So at the end of “Hey You” he makes this cry for help, but it’s too late.

TV: Because he’s behind the wall?

RW: Yeah, and anyway he’s only singing it to himself, you know, it’s no good crying for help if you’re sitting in the room all on your own, and only saying it to yourself. All of us I’m sure from time to time have formed sentences in our minds that we would like to say to someone else but we don’t say it, you know, well, that’s no use, that doesn’t help anybody, that’s just a game that you’re playing with yourself.

TV: And that’s what comes up on the track “Nobody Home,” the first line being “I’ve got a little black book with my poems in.”

RW: Yes, exactly, precisely, yeah, after “is there anybody out there” which is really just a mood piece.

TV: So he’s sitting in his room with a sort of realization that he needs help, but he doesn’t know how to get it really.

RW: He doesn’t really want it.

TV: Doesn’t want it at all?

RW: Yeah, well, part of him does, but part of him that’s you know, making all his arms and legs, that’s making everything work doesn’t want anything except just to sit there and watch the TV.

TV: but in this track “Nobody Home” he goes through all the things that he’s got: “he’s got the obligatory Hendrix perm…” all the things that we know are pretty real in the world of rock and roll.

RW: There are some lines in here that harp back to the halcyon days of Syd Barret, it’s partly about all kinds of people I’ve known, but Syd was the only person I used to know who used elastic bands to keep his boots together, which is where that line comes from, in fact the “obligatory Hendrix perm” you have to go back ten years before you understand what all that’s about.

TV: Now when he says I’ve got fading roots at the very end…

RW: Well, he’s getting ready to establish contact if you like, with where he started, and to start making some sense of what it was all about. If you like he’s getting ready here to start getting back to side one.

TV: Which he does via the next track which is called “Vera,” very much World War II…being born and created if you like in that era again.

RW: This is supposed to be brought on by the fact that a war movie comes on the TV.

TV: Which you can actually hear?

RW: Mentioning no titles or names! Which you can actually hear, and that snaps him back to then and it precedes, what is for me anyway, is the central song on the whole album “Bring the Boys Back Home

TV: Why?

RW: Well, because it’s partly about not letting people go off and be killed in wars, but it’s also partly about not allowing rock and roll, or making cars or selling soap or getting involved in biological research or anything that anybody might do, not letting that become such an important and “jolly boys game” that it becomes more important than friends, wives, children, other people.

[IS THERE ANYBODY OUT THERE?]

[NOBODY HOME]

[VERA]

[BRING THE BOYS BACK HOME]

TV: So physiologically what stage of the character Pink for the track “Comfortably Numb”?

RW: After “Bring the Boys Back Home” there is a short piece where a tape loop is used; the teachers voice is heard again and you can feel the groupie saying “are you feeling ok” and there’s the operator saying, er, “there’s a man answering” and there’s a new voice introduced at that point and there’s somebody knocking on the door saying “come on it’s time to go,” right, so the idea is that they are coming to take him to the show because he’s got to go and perform that night, and they come into the room and they realize something is wrong, and they actually physically bring the doctor in, and “Comfortably Numb” is about his confrontation with the doctor.

TV: So the doctor puts him in such a physiological state that he can actually hit the stage?

RW: Yes, he gives him an injection, in fact it’s very specific that song.

TV: “Just a little pinprick”?

RW: Yeah.

TV: “There’ll be no more aaaaaaaaaaah!”

RW: Right.

[COMFORTABLY NUMB]

RW:Because they’re not interested in any of these problems, all they’re interested in is how many people there are and tickets have been sold and the show must go on, at any cost, to anybody. I mean I, personally, have done gigs when I’ve been very depressed, but I’ve also done gigs when I’ve been *extremely* ill, where you wouldn’t do any ordinary kind of work.

TV: Because the venue is there and because the act’s there…

RW: And they’ve paid the money and if you cancel a show at short notice, it’s expensive.

TV: So the fellow is back in the stage, but he’s very…I mean he’s vicious, fascist.

RW: Well, here you are, here is the story: I’ve just remembered; Montreal 1977, Olympic Stadium, 80,000 people, the last gig of the 1977 tour, I, personally, became so upset during the show that I *spat* at some guy in the front row, he was shouting and screaming and having a wonderful time and they were pushing against the barrier and what he wanted was a good riot, and what I wanted was to do a good rock and roll show and I got so upset in the end that I spat at him, which is a very nasty thing to do to anybody. Anyway, the idea is that these kinds of fascist feelings develop from isolation.

TV: And he evidences this from the center of the stage?

RW: This is him having a go at the audience, all the minorities in the audience. So the obnoxiousness of “In the Flesh” and it is meant to be obnoxious, this is the end result of that much isolation and decay.

[THE SHOW MUST GO ON]

[IN THE FLESH]

TV: And then seemingly in the track “Run like Hell” this is him telling the audience…?

RW: No…

TV: Is this him telling himself?

RW: No, “Run like Hell,” is meant to be him just doing another tune in the show. So that’s like just a song, part of the performance, yeah…still in his drug-crazed state.

[RUN LIKE HELL]

RW:After “Run like Hell” you can hear an audience shouting “Pink Floyd” on the left-hand side of the stereo, if you’re listening in cans, and on the right-hand side or in the middle, you can hear voices going “hammer” they’re saying ham-mer, ham-mer…This is, the Pink Floyd audience, if you like, turning into a rally.

TV: And then comes the track “Waiting for the Worms,” the worms in your mind are decay, decay is imminent.

RW: “Waiting for the Worms” in theatrical terms is an expression of what happens in the show, when the drugs start wearing off and what real feelings he’s got left start taking over again, and he is forced by where he is, because he’s been dragged out his real real feelings. Until you see either the show or the film of this thing you won’t know why people are shouting “hammer,” but the hammer, we’ve used the hammer as a symbol of the forces of oppression if you like. And the worms are, the thinking part. Where it goes into the “waiting” sections…

TV: “Waiting for the worms to come, waiting to cut out the deadwood.”

RW: Yeah, before it goes “waiting to cut out the deadwood” you hear a voice through a loud-hailer, it starts off, it goes “testing, one two,” or something, and then it says “we will convene at one o’clock outside Brixton Town Hall,” and it’s describing the situation of marching towards some kind of National Front rally in Hyde Park. Or anybody, I mean the National Front are what we have in England but it could be anywhere in the world. So all that shouting and screaming… because you can’t hear it you see, if you listen very carefully you might hear, er, Lambeth Road, and you might hear Vauxhall Bridge and you might hear the words “Jewboys,” er, “we might encounter some Jewboys” it’s just me ranting on.

[WAITING FOR THE WORMS]

TV: Who puts him on trial?

RW: He does.

TV: He puts himself on trial?

RW: Yes. The idea is that the drugs wear off and in “Waiting for the Worms” he keeps flipping backwards and forwards from his real, or his original persona if you like, which is a reasonably kind of humane person into this waiting for the worms to come, persona, which is crack!, flipped, and is ready to crush anybody or anything that gets in the way… which is a response to having been badly treated, and feeling very isolated. But at the end of “Waiting for the Worms” it gets too much for him, the oppression and he says “stop.” I don’t think you can actually hear the word “stop” on the record, or maybe you can, anyway it goes “STOP,” yeah, it’s very quick, and then he says “I wanna go home, take off this uniform and leave the show,” but he says “I’m waiting in this prison cell because I have to know, have I been guilty all this time” and then he tries himself if you like. So the judge is part of him just as much as all the other characters and things he remembers…they’re all in his mind, they’re all memories, anyway, at the end of it all, when his judgment on himself is to de-isolate himself, which in fact is a very good thing.

TV: So now it has really turned full circle.

RW: Almost, yeah. That kind of circular idea is expressed in just snipping the tape at a certain point and just sticking a bit on the front, that tune, you know this “Outside the Wall” tune, at the end.

TV: So the character in “outside the Wall” says “all alone, or in two’s…mad buggers wall,” and that really is the statement of the album.

RW: And which I have no intention of even beginning to explain.

[THE TRIAL]

[OUTSIDE THE WALL]

TV: Roger, what will it actually be like when we see “The Wall” in concert?

RW: Just like it normally is for a lot of people, who’re all packed behind PA systems, and things, you know like, every seat in the house is sold so there’s always thousands of people over the site who can’t see anything, and very often in rock and roll shows the sound is dreadful, because, because it costs too much to make it really good, in those kind of halls, you know, the sound will be good mind you in these shows, but the impediments to seeing what’s going on and hearing what’s going on will be symbolic, rather than real, except for the wall, which will stop people seeing what’s going on.

TV: Is the wall going to remain there?

RW: No, not forever.

TV: Who’s going to knock it down?

RW: Well, I think we should wait and see about that, for the live show, I think it would be silly really for me to explain to you everything that’s going to happen in the live show that we put up, mind you, anybody with any sense listening to the album will be able to spot whereabouts in the show it is that it comes down!

TV: That’s the physical wall, what about the physiological wall?

RW: Ah, well, that’s another matter, whether we make any in-roads into that or not, is anybody’s guess. I hope so.

TV: Roger Waters describing The Wall.